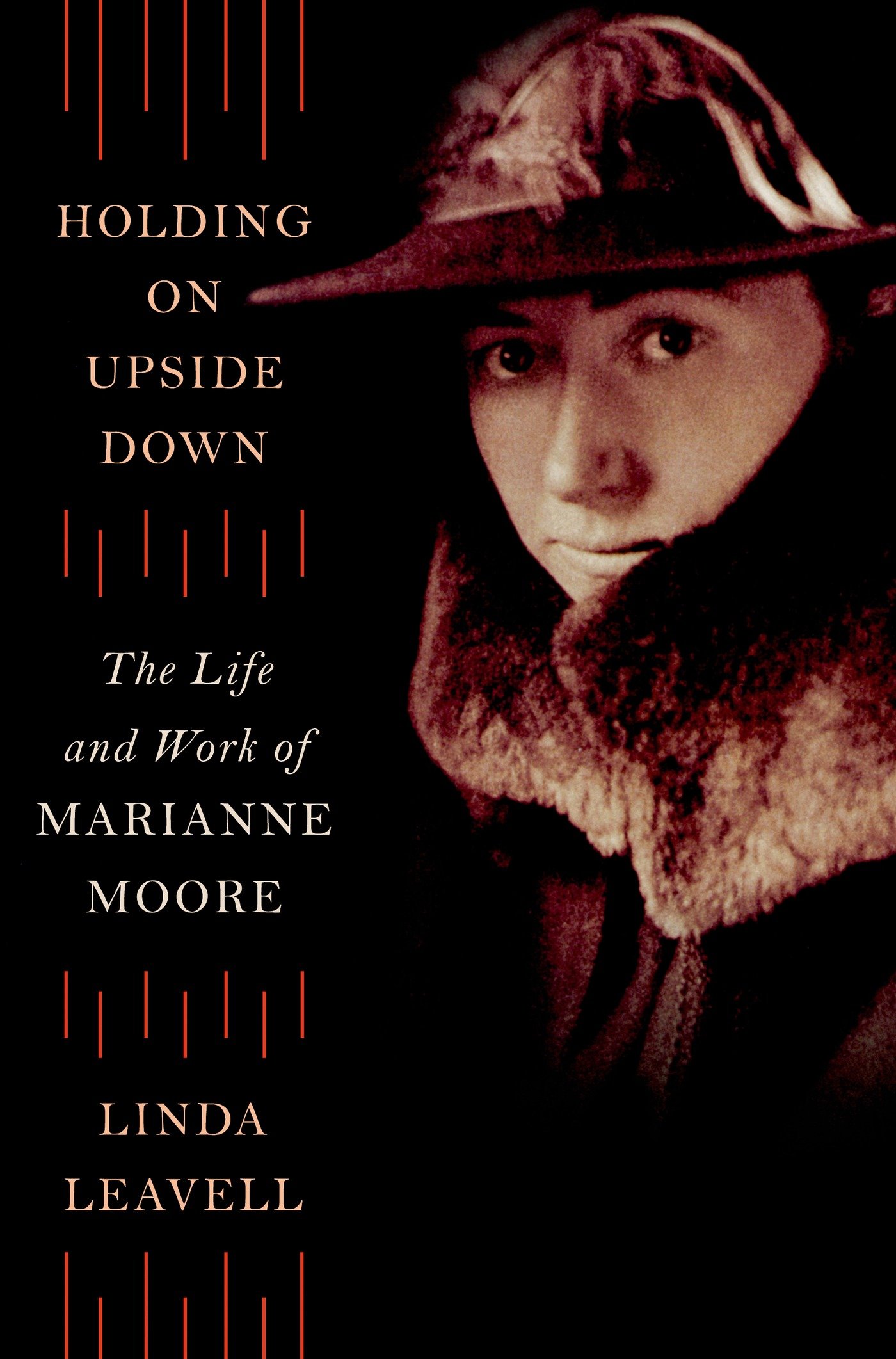

Holding On Upside Down: The Life

Holding On Upside Down: The Life

and Work of Marianne Moore

by Linda Leavell

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

480 pages, $30.

IT’S AN ARRESTING ODDITY: the fact that a leading American poet made a home with her mother for most of her adult life. Certainly no other woman poet from the past century—Louise Bogan, Muriel Rukeyser, Elizabeth Bishop, Adrienne Rich—lived so closely tied to her mother’s physical presence, though some (such as Bishop) were haunted by their mother’s absence. And so the title of Linda Leavell’s expansive and eye-opening biography, Holding On Upside Down, suggests a life that, like Marianne Moore’s poetry, involved the unusual.

Leavell, who lives in Fayetteville, Arkansas, has spent decades studying her subject, and an earlier work on Moore and the visual arts received critical acclaim. Holding On has broader scope, beginning with a brief family history and continuing to the poet’s death in 1972 at age 85. Leavell’s main sources were not only published and unpublished poems but also commonplace books filled with notes and clippings that Moore wove into her poetry, as well as correspondence with several thousand relatives and friends. Relevant photographs and a usefully pruned family tree complement the text, and the well-organized materials create an engaging sense of how Moore lived, and how she wrote.

And write she did. From the verses she wrote in college to poetry published in her seventies, Moore observed, researched, reflected, and composed. Her watchwords were “perseverance,” “relentless accuracy,” and “fortitude.” The Collected Poems (1951) received a Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the Bollingen Prize. Moore was an early modernist whose writing evolved from complex images and obscure references to more readily accessible poetry. At the height of her fame, she was not only recognized but distinguished, receiving an honorary doctorate from Harvard (1969), her sixteenth such accolade.

She did all of this while living under her mother’s intense gaze for close to sixty years. More than half of the book is devoted to these years. What bound Moore to such a life? While Leavell presents evidence rather than psychoanalysis, she does offer some clues. Marianne’s parents separated before her birth, when her father became “consumed with a religious obsession.” Marianne was born near St. Louis, but her mother Mary Moore raised her and an older brother, Warner, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where Mary taught English in the children’s school. Words were the family’s amusement, especially nicknames. After mother, daughter, and son read The Wind in the Willows, for example, they became “mole,” “rat” (or “ratty”), and “Mr. Badger” to each other.

The three family members were close, tracking each other’s friendships, opinions, and plans. This intimacy was tested in the fall of 1900, when Mary Moore fell deeply in love with Mary Norcross, the youngest daughter of Car-lisle’s Presbyterian minister, who loved her back. Based on their letters, Leavell makes it clear that the women’s relationship was physical and fully realized, and, while they did not combine their households, they were always in each other’s company.

Warner and Marianne, now teenagers, were wary of the new woman in their moth-er’s life, but a vacation in Maine helped turn t hings around. At the suggestion of a friend, the four traveled to Monhegan Island, an idyllic setting of rocks and sea to which they would often return, and which would inspire some of Moore’s most imaginative work (such as her poem “The Fish”). A photo of the two Marys sitting with Marianne shows beaming faces. Norcross became the shy girl’s confidante, taking up a role somewhere between second parent and older sister, Leavell says, and helped her build a social life at Bryn Mawr.

hings around. At the suggestion of a friend, the four traveled to Monhegan Island, an idyllic setting of rocks and sea to which they would often return, and which would inspire some of Moore’s most imaginative work (such as her poem “The Fish”). A photo of the two Marys sitting with Marianne shows beaming faces. Norcross became the shy girl’s confidante, taking up a role somewhere between second parent and older sister, Leavell says, and helped her build a social life at Bryn Mawr.

Alas, little more than a decade later, the idyll was to end when Norcross fell in love with another woman. As Leavell tells the story, Mary Moore, now close to 50, was devastated. By then, Warner had left for work in New Jersey. His sister, who had graduated and was already submitting poems for publication, had been offered a job in the library at Columbia University. However, partly at Norcross’ urging, Marianne decided instead to stay in Carlisle and act as helpmate to her bereft mother. When Warner became pastor of a church in Chatham, New Jersey, a few years later, he invited his mother and sister to live with him, and they accepted.

Leavell points out that Chatham was just an hour by train from New York City, where publishing flourished, so it’s not surprising that, when Warner announced he would be getting married, Moore and her mother began to look for housing there. With a limited budget, they settled on a one-room apartment in Greenwich Village, with space for a sofa, a bed and two chairs, but with little light, no phone—and no kitchen! After a decade, the women moved to roomier quarters in Brooklyn, but they continued to share a bedroom so as to have a “spare room” in case “Mr. Badger” (i.e., Warner) wanted to stay over.

Moore held part-time library and editorial jobs over the years, but was otherwise in residence with her mother. As Leavell tells it, the poet “had no privacy at home, no ‘room of her own,’” while her mother, having “longed for intimacy” as a child, “recognized no need for [her child’s]privacy.” The pair’s closeness extended to Moore’s poetry and prose, for which Mary was first reader, critic, and editor. And they traveled together. Keeping healthy was a struggle (at one point Moore weighed less than eighty pounds). Yet, under these cheek-by-jowl conditions, Moore built a flourishing literary life. How did she do it?

For one thing, Leavell suggests, she had an unquenchable impulse for poetizing, declaring in a letter home from college that she felt ineluctably “possessed to write.” In the years that followed, writing seemed to become the poet’s means of survival. Her mother supported her ambitions, serving as household cook, laundress, seamstress, and co-hostess for frequent visitors. Moore didn’t always welcome her mother’s help but managed to write some feelings into poetry—thus, the poem “Marriage,” which Leavell calls a “mock epithalamium” and which addresses her complex and paradoxical relationship with her mother (who sometimes in the 1920s referred to her daughter and herself as a “young couple”). Over time, Moore came to value her mother’s help. In “The Paper Nautilus,” written years after “Marriage,” the poet implies that, just as a female nautilus encases her eggs in a shell to protect them, her mother had imposed conditions that supported a poetic life: a rigorous attention to words and their meaning, the right mix of visitors, sufficient food and sleep.

Moore’s energies were focused, her efforts driven. Soon after arriving in New York, for example, she called on the gallery owner and photographer Alfred Stieglitz, forging links to the city’s art world. She repeatedly pursued conversations with Scofield Thayer, editor of the literary journal The Dial, who would eventually hire her as the magazine’s editor. She sought advice from poets whose work she liked, and as her poetry was published, her admirers proliferated, among them Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, H.D., William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, and W. H. Auden. Robert Frost offered to help publish her poems, and John Ashbery praised their “tense, electric clarity.” Moore counseled Elizabeth Bishop, and they became lifelong friends. Meeting the older poet had “influenced the whole course” of her life, Bishop said, calling her mentor’s poems “miracles of construction” that are “clear and dazzling.”

Moore also gained the affection of lesser writers, some of whom became her patrons. A gay couple—museum director and novelist—were among Moore’s and her mother’s dearest friends, and a lesbian couple became family to Moore after her mother died. Louise Crane, Bishop’s onetime lover, was executor of Moore’s estate. Yet, while she had crushes, mainly on women, in her younger days, Moore never forged a romantic partnership, once musing to an interviewer that perhaps hers was a case of “arrested emotional development.”

What she did make, in abundance, was poetry. Although her fame ebbed with the arrival of feminist or confessional poets such as Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and Adrienne Rich, Moore’s poetry is being noticed anew for its uniquely rhymed stanzas, its departure from sentimentality, its directness, and its verve. She valued individual liberty, fairness, direct words, and tolerance. With this careful and comprehensive biography Leavell sets the poet in an inviting light for reexamination and acclaim.

Rosemary Booth is a writer and photographer living in Cambridge, Mass.